Becoming in the Ruins: Myth, Theosis, and Symbolic Collapse in ‘Neon Genesis Evangelion’

1. Introduction

Neon Genesis Evangelion (新世紀エヴァンゲリオン; literally “New Century Evangelion” or “Good News of a New Beginning”) (1994–2023) is a paradoxical franchise. At once hailed as a landmark of psychological depth and postmodern storytelling, it has also persistently proved to be a frustration to its creator, Hideaki Anno, who has variously claimed that much of its symbolism was arbitrary, even empty. The show and its subsequent works have inspired massive fanbases, but it has also equally brought forth deep criticism and resentment, often blocking access to the world of manga and anime in toto, acting as a kind of filtering gatekeeper to those who experience it as a defining summit. The show’s visual lexicon — replete with crosses, angels, and apocalyptic prophecy — suggests a mythic depth, while its actual narrative frequently dissolves into individualistic abstraction, trauma, and surrealist disjunction.

Yet despite — or because of — this ambiguity, Evangelion has become one of the most analyzed, reinterpreted, and emotionally formative anime series of all time. The show exemplifies what philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer called the “fusion of horizons,” where meaning emerges not solely from the author’s intention but from the historically situated encounter between text and interpreter. Indeed, in some ways, to “interpret” Evangelion is to “interpret” the life of Anno himself, for as he has stated: “Evangelion is my life and I have put everything I know into this work. This is my entire life. My life itself.”1

Although Evangelion in some sense may then be thought of as a work of autobiography, it would be best to consider it as something like “Myth as Autobiography of the Soul.” This is because Evangelion is encoded with the existential crises and depression that made up the life of Anno at the time. Thus, depression, social alienation, suicidal ideation, objectification, egoism and the like are not “themes” of Evangelion, but rather the symbolic narrative infrastructure of the work. The “world” of the franchise is more like unto a psychic landscape, populated less by characters, but more by archetypes of the fragmented self and identity of Anno himself. It is also something like a “Myth as Cultural Mirror” where the post-bubble Japanese psyche undergoes an x-ray and its bones become the scaffolding of this franchise.

Thus to understand Evangelion as a mythological text, one must first ask: What is myth, and what does mythmaking mean from the mind of one firmly rooted in the modern and postmodern paradigm? In pre-modern cultures, myths structured reality. They encoded cosmologies, social roles, and archetypal patterns. But the modern project of rationality — coupled with the traumas of global war, genocide, and technological disintegration — produced a fractured variation of this integrative function. As Jean-François Lyotard has observed, and as has become one of the most common remarks on the subject, postmodernity is marked by “incredulity toward metanarratives.” Nonetheless, this mythmaking pattern of being is inescapable. Thus, instead of escaping mythmaking, postmodern myths are often tirelessly reflexive myths about the lack of need for myths. As Claude Lévi-Strauss put it in his essay The Structural Study of Myth,

Since the purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction (an impossible achievement if, as it happens, the contradiction is real), a theoretically infinite number of slates will be generated, each one slightly different from the others. Thus, myth grows spiral-wise until the intellectual impulse which has originated it is exhausted. Its growth is a continuous process, whereas its structure remains discontinuous. If this is the case, we should consider that it closely corresponds, in the realm of the spoken word, to the kind of being a crystal is in the realm of physical matter. This analogy may help us understand better the relationship of myth on one hand to both langue and parole on the other.2

This is exactly how Evangelion has developed — beginning as a single TV series, but fracturing into alternate endings, films, rebuilds, manga adaptations, and more. Each version retells the same essential narrative but with slight variations, like crystalline facets cut at different angles. The original contradiction — how to live with oneself and others in a world defined by trauma, estrangement, and unhealed wounds — is never “solved,” but revisited, reconfigured, and re-expressed. Anno doesn’t resolve Shinji’s dilemma — he spirals around it. From the breakdown of narrative structure in episodes 25–26 to the visual excess of End of Evangelion and the bittersweet reflection of the Rebuild series, the entire corpus behaves like Lévi-Strauss’s mythic spiral: driven by the same psychic impulse, generating infinite “slates,” each variation probing the same unspeakable tension.

Indeed, in the post-modern context that spawned Evangelion, replete with the reactive depressive and anxious loss of meaning, one could say that the form of the franchise, the symbolic form of mythmaking as Lévi-Strauss saw it, and the form of the social condition were all functioning in parallel on the same circuit! Evangelion doesn’t just depict postmodern disintegration, it performs it — both a symptom and structure of its time. In fact, Jonathan Pageau, commenting on the work of Dante on his Symbolic World podcast, has noted that it has had a profound impact on him: specifically in understanding the way that the universal has to be obtained through both one’s personal narrative as well as the “personal narrative” of the nation that one lives in.3 And in the same episode, Jonathan comments on the significance of The Divine Comedy standing as a work transitioning between the medieval synthesis and the Enlightenment, thus allowing the work to bring to the fore the “live” issues at stake for the society that bore it. In its own way Evangelion is standing at a crossroad between postmodernity and meta-modernity.

2. Evangelion as a Psychic Landscape

On its surface, the plot is deceptively archetypal for a pop-culture work from Japan: teenagers pilot giant biomechanical mechs (Evangelions) to defend Earth from mysterious “Angels.”4 But beneath this premise lies a deep rupture: the absence of stable meaning. Angels are not divine; God is silent; humanity’s technological progress leads only to further alienation. The “meta-narratives” that are in conflict throughout modernity, the air that Japan was living under, resolve unto silence in the face of meaninglessness. The Instrumentality Project — a radical plan to dissolve all individual consciousnesses into a single, unified existence, erasing personal boundaries in a bid to overcome human suffering, loneliness, and the fear of rejection — offers a dark and obviously hollow transcendence only through annihilation of the self.

What the franchise faces is Apocalypse no longer as a cosmic drama, but rather as a psychological Event. The final episodes of the original series do not culminate in a climactic battle, but in protagonist Shinji Ikari’s descent into his own fractured psyche. This internalization of the mythic echoes Joseph Campbell’s “hero’s journey,” but inverts it: instead of returning with wisdom, Shinji confronts only the shattered fragments of his identity, the void at the center of selfhood. It equally symbolizes the movement through puberty, not as an adventure which reintegrates wisdom through its passage, but rather the Event which, through distance and reflection, can inspire wisdom itself. But this Apocalypse is deceptive in that it truly is a grappling with the violence inherent in the paradigm, but represented through the “mere” status of developing through puberty, and its fractal image of “trauma.” And what’s more: this “trauma” of puberty is itself a symbolic reflection of the author’s “trauma” of depression.

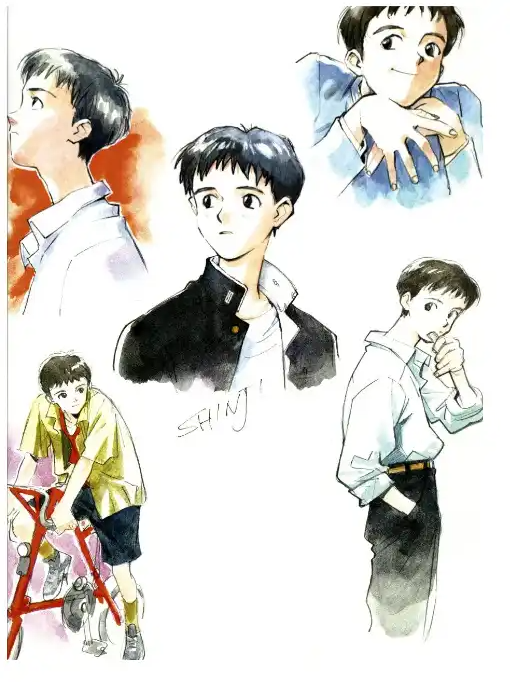

Shinji Ikari is perhaps the most anti-heroic protagonist in the history of science fiction. He is not brave or self-sacrificing. He is avoidant, depressive, emotionally fragile, often downright repellent. And yet, it is precisely Shinji’s failure to fulfill the expectations of the modern heroic subject that makes him the site of the Apocalypse-Event of late 20th-century existential crisis.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, Shinji embodies a collapse of symbolic structures. His mother is absent, literally subsumed into the Eva Unit he must pilot. His father is distant, manipulative, and tyrannical — Gendo Ikari, the archetypal devouring superego. The women around him — Rei, Asuka, Misato — each function not as a fully coherent agent but as a distorted projection of either maternal, sexual, or anima archetypes. There is no genuine intimacy in Shinji’s world; only broken attempts at contact, always refracted through fear and shame. It is deeply and unavoidably egotistical — to the point of viewing all as objects in the cosmology of the ego. In some sense, it explicitly reveals the failure of these paradigms to do aught but navel-gaze.

Shinji’s psychological paralysis, however, is not incidental — it is a theological condition. He exists in the quintessential modern world where the sacred has “collapsed” and yet where the promise of science offers no salvation. The Eva units themselves, grotesque fusions of machine and flesh, are not symbols of heroic control but of repressed trauma and monstrous birth. Their very design — humanoid yet uncanny, mechanical yet organic — embodies the uncanny return of the repressed. They are not instruments of redemption, but icons of paradigmatic inversion: “liturgical” vessels without grace, incarnations without logos, sacraments of technological despair. Each Eva is a false theophany — a parody of the Incarnation — where flesh and spirit are conjoined not through love, but through control, coercion, and containment. In place of Christ taking on human nature to heal it, we see mothers consumed, children weaponized, and the body rendered as a site of psychic violation. The Eva is not the image of God but the mirror of a world that has forgotten Him — a world in which transcendence is simulated, and power is mistaken for presence. It is through these monstrous vessels that Shinji is asked to save the world, and in doing so, he is not elevated, but further entangled in a sacrilegious “liturgy” of pain. His paralysis, then, is not weakness — it is the scream of a soul confronted with a false god and asked to become its priest.

This is where the central irony of Evangelion comes from: it traffics in dense symbolic language — crosses, the Lance of St. Longinus, Kabbalistic trees — yet its creator repeatedly denies any theological import. Anno has claimed that Christian imagery was chosen for its “exotic” visual impact in a Japanese context. This admission has led some to dismiss the symbolism as superficial.

But such dismissal misses a crucial point: symbolism is not reducible to intention. As Jonathan Pageau notes, symbols operate on a level deeper than rational design: “Symbolism Happens.” They arise from the confluence of cultural memory, archetypal resonance, the unconscious, the actual structure of the world and the means of our meaning-making capabilities. In Evangelion, the cross is not simply a Christian artifact — it becomes a floating signifier, a haunted relic of meaning whose original referent has been evacuated from the characters within the world, but yet to the viewer, its meaning as symbol is clear. There is something of a metatextual dramatic irony at play here.

The show’s symbolic vocabulary, though fragmented, speaks to deep intuitions: that suffering must have meaning, that the self is multiple and unstable, that love is both salvific and terrifying. It offers no metaphysical certainties, but it does not itself lapse into nihilism either, despite often depicting the conclusions of it. Instead, it dramatizes the very process by which we seek meaning in a disenchanted world.

In its broken narrative, its unresolved trauma, and its mythic yet self-canceling symbolism, Neon Genesis Evangelion maps the psychic landscape of the postmodern subject. Yet unlike much of postmodern art, which embraces irony through detachment, Evangelion turns inward, toward pain, desire and longing. The irony is punctuated, and serves a purpose of jolting the viewer almost as if a postmodern koan. Indeed, Anno himself has stated:

The fact that you see salarymen reading manga and pornography on the trains and being unafraid, unashamed or anything, is something you wouldn’t have seen 30 years ago, with people who grew up under a different system of government. They would have been far too embarrassed to open a book of cartoons or dirty pictures on a train. But that’s what we have now in Japan. We are a country of children.5

The quote itself provides a deeply discomforting set of images. One would think, “Of course I’m happy that an adult can read a comic book without feeling ashamed in public.” But the flipside of that, I suspect, few would argue for. Yet the conclusion, that Japan is a country of children, holds no small weight for the Evangelion franchise, which retains the symbolic structure of Apocalypse as being fractally a passage through puberty now reflected onto the totality of Japan’s national spirit.

3. Theological Crisis and False Union

The End of Evangelion (1997) functions not only as a cinematic coda to the original series but as its mirror — a crucible in which the abstract psychological narrative of episodes 25 and 26 of the original series is externalized into violent spectacle, cosmic horror, and metaphysical rupture. Where the final episodes of the television series withdrew into Shinji’s inner world, The End assaults the viewer with a material and symbolic cataclysm, forcing confrontation with all that was suppressed, fragmented, or implied. Rather than simply depicting the destruction of the world, The End of Evangelion dramatizes the destruction of narrative coherence itself. Time fractures. Characters dissolve. Language fails. The fourth wall buckles and collapses. We do not witness “what happens” — and to ask about it at a narrative level seems to miss the point — but rather the unmaking of meaning; the moment when not only the world but the subject unravels. And in this unraveling, paradoxically, Evangelion begins to reconstruct something like myth, revealing yet again its existential necessity.

Indeed, the very postmodern drive is pushed to its absolute limit in The End of Evangelion, where, in the midst of this narrative and symbolic collapse, it turns its gaze outward, breaking the fourth wall to address its cry not only to its characters but to its audience. Live-action footage, scribbled notes, animation drafts, and audience shots puncture the diegesis, rendering the film a mirror held up to those watching it. Characters like Shinji and Rei speak not only to each other, but to “you,” the viewer, their questions doubling as challenges to passive spectatorship. The film’s most jarring images — Shinji’s shameful violence, Asuka’s brutalized body, or the hauntingly ambiguous line “kimochi warui” (“How disgusting”) — function not as spectacle but indictment. Evangelion doesn’t “merely tell a story” — rather, its myth always-already contains within it the doubling out of address — metafictional, emotional, and deeply uncomfortable. It does not offer closure, but rather demands reckoning. Indeed, as critic Hiroki Azuma writes of the work,

From the outset, the anime Evangelion was launched not as a privileged original but as a simulacrum at the same level as derivative works. In other words, this thing that Gainax was offering was certainly more than a single grand narrative, with the TV series as an entrance. Rather, it was an aggregate of information without a narrative, into which all viewers could empathize of their own accord and each could read up convenient narratives. I call this realm that exists behind small narratives but lacks any form of narrativity a grand nonnarrative, in contrast to Otsuka’s “grand narrative.” Many consumers of Evangelion neither appreciate a complete anime as a work (in the traditional mode of consumption) nor consume a worldview in the background as in Gundam (in narrative consumption): from the beginning they need only nonnarratives or information.6

At the heart of The End of Evangelion is the Human Instrumentality Project — a metaphysical event in which all singular consciousnesses are absorbed into a single, undifferentiated field of being. The many individualities would be absorbed into the singular individuality of larger scope, not of a higher order. This is no mere sci-fi flourish; it is the series’ philosophical fulcrum. Instrumentality is depicted as “the form of salvation” within the paradigm of late modern Japan, and yet at the same time, it is a profound nightmare. This is because the missing Christ from the center of the world, from suffering, from the shedding of the ego-self, and even from submitting oneself to “the highest good” does in fact render them pointless. Rather, Instrumentality is a dramatic, world-consuming expression of utilitarianism taken to its extreme. That is because it is a moral logic in which the greatest good is understood as the elimination of suffering for the greatest number — even at the cost of personal identity, freedom, or love. It offers the most “logical” escape from the loneliness, fear, shame, and the pain of separation that flow from the type of egocentrism that flows from Shinji — echoing, in part, Buddhist notions of liberation from the “illusion of self.”

But viewed from a Christian standpoint, its cost is staggering: the annihilation of personal identity, the collapse of boundaries, the erasure of relational particularity through which Love itself is “effectively eliminated.” This represents a false and tragic parody of what true ego-death is and what true union is meant to be. Crucially, End of Evangelion does not ultimately endorse this dissolution — Shinji, in the end, rejects Instrumentality. He cannot go through with the merger. The narrative itself withholds affirmation of the very union it offers, underscoring the deep incoherence and spiritual poverty of that vision. In the Orthodox vision, humanity is called to communion with God in Christ — not by being dissolved into an abstract oneness, but by being drawn into the divine life in such a way that each person becomes the unique expression of Christ they were created to be. Ultimately, the “ego-death” represented in Evangelion is a more subtle continuation of the ego: much like the historical move to Protestantism is itself a more subtle continuation of the logic of Catholicism, and atheism is itself a more subtle continuation of the logic of Protestantism. Dialectically, these moves “make sense” and are “rational” at the highest level, resolving logical tensions into more tightly entangled webs. But ultimately the “resolution” is that which leaves intact the implicit clinging to the “knot,” but ultimately aiming to “simply make it as tight as possible.” But really, while rightly complaining of the “knottedness,” the project of simply resolving to tighten it as much as possible as “the best possible failure” is still a failure. What is needed ultimately is the mighty sword of Alexander the Great to brutally slice the Gordian Knot in half and free us from its yoke.

This is ultimately the mystery of theosis in the Christian tradition: not the erasure of personhood, but its fulfillment through union. As St. Maximus the Confessor teaches, the one Christ is made manifest differently in each of His members — the vast sameness of Christ infinitely differentiated, like a single light (Logos) refracted through countless facets (logoi). The saints do not vanish into divinity; they are transfigured by it, each one bearing the uncreated light in a way that is irreducibly their own, yet unconfusedly Christ. Union with God, then, does not collapse personhood — it exalts it in Love.

Where Instrumentality seeks peace through fusion and the obliteration of difference, Christian union offers peace through Love that preserves distinction and freedom, which deepens personhood. In Christ, the many are made one — but not through erasure. Rather, in the Body of Christ, each member retains its unique function and identity: the hand is not the eye, the eye not the ear, and yet all are harmonized in a symphony of divine life. As St. Maximus affirms, the unity of the Church is not monotony, but the radiant unfolding of the one Logos in infinite personal forms. Evangelion’s Instrumentality, by contrast, becomes an eschatological warning — a vision of union sought apart from True Love, apart from communion, apart from the face of the Other, apart from Love. It is a pseudo-salvation that replaces intimacy with absorption, and freedom with dissolution. The True Path is not sameness, but sacramental communion: the sharing of Being in which each person becomes fully themselves in and through the life of the other, without fear, without true loss, without end.

4. Gender, Power, and the Wound of the Feminine

But of course, one of the key elements of the work is the fact that it takes place in and through Shinji, who is not himself a holy man striving for enlightenment — but rather a child of abandonment, loss, and shame, desperate for connection and terrified of intimacy.

Shinji, when offered the choice to merge with all humanity or reclaim his discrete self, stands at the crossroads of metaphysical being and psychological integrity. And here lies the deepest theological question Evangelion raises: is the self a prison, or is it a gift? Simultaneously the metatextual problem which we have already discussed is that this ultimate question is conditioned by the predetermined cultural limits which generated it. Thus in choosing personhood over this false union, Shinji refuses both the obliteration of pain and simultaneously the obliteration of possibility. He acknowledges that the path to Love and the suffering it entails are two sides of the same coin. However, the meaning of love as present in the work itself, as from the given paradigm — that to be human is to bear the burden of separateness, not to escape it — is actually far different from the interpretation most often represented by its fans. Thus, no analysis of Evangelion is complete without reckoning with its complex — and at times deeply troubling — portrayal of the feminine. In The End of Evangelion, the central female figures — Rei Ayanami, Asuka Langley Soryu, Misato Katsuragi, and Yui Ikari — each embody archetypal dimensions of the divine feminine, not in harmony but ultimately in conflict, not as passive ideals but as ruptures in the consciously broken symbolic order.

Rei — a mysterious and emotionally distant pilot whose enigmatic connection to Shinji’s father and her symbolic mirroring of Shinji’s own isolation make her both a reflection and a catalyst for his existential introspection — becomes a kind of cosmic vessel, a figure through whom the Instrumentality process is initiated. Her fusion with Lilith transforms her into the symbol of the mother-goddess, both nurturing and terrifying. She is the anima mundi, the world soul — but, emptied of personality, she also reveals the horror of undifferentiated being.

Asuka — a brash, competitive Eva pilot who antagonizes Shinji and drags his buried insecurities to the surface — becomes an avatar of rage, wounded pride, and raw survival instinct when she is violently reanimated in her final stand against the Mass Production Evas. Her final battle is operatic, an eruption of will against a faceless, entropic onslaught. But it is not a triumph in the traditional sense. It is defiance against absorption, a scream against annihilation. In Jungian terms, she channels the Terrible Anima: fierce, unyielding, and fractured by the collapse of paternal order. She is Athena divested of wisdom, a goddess of war animated solely by fury.

Misato, Shinji’s guardian and NERV operations director, serves as a flawed but caring surrogate parent figure, embodying the tension between emotional intimacy and adult dysfunction that shapes much of Shinji’s struggle for connection and identity. She straddles the roles of mother, lover, and warrior, and thereby represents the tragic failure of “secular” integration. Her attempt to guide Shinji is riddled with contradictions — seduction entangled with maternal care, purpose undermined by personal despair. She is a woman whose attempts to preserve order are themselves corroded by the very systems she serves.

Yui Ikari, Shinji’s mother and the spirit enshrined in Eva Unit-01, is perhaps the most mystically charged character. She is simultaneously absent and omnipresent, maternal and transcendent. Yui ultimately chooses not to return to her human form, instead becoming a kind of eternal witness floating through space — a cosmic un-Eve reborn as pure potential rather than flesh. A kind of Buddhist rejection of the flesh, yet with a radical attachment to humanity, such that her “transcendence” is a monument to herself as being “that one person” who will live forever as proof of mankind’s existence.

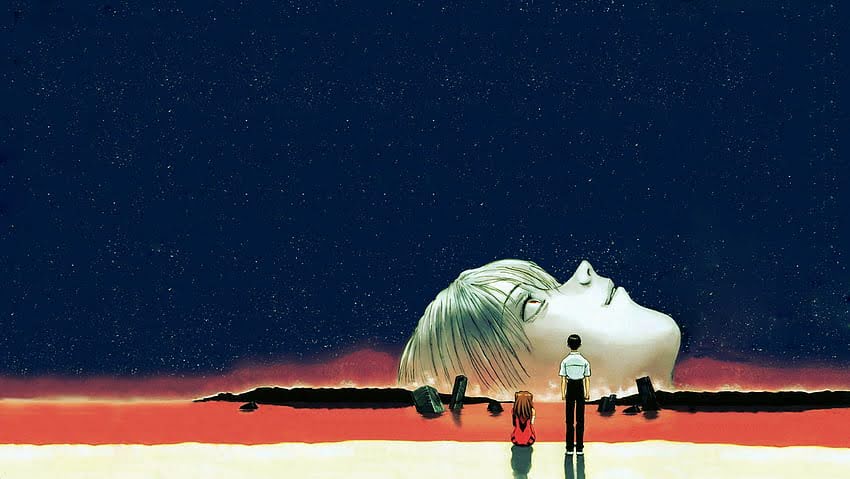

The final moments of The End of Evangelion are notoriously opaque. After the collapse of individual boundaries in Instrumentality, Shinji reconstitutes himself on the shore of a ruined world. The sea is red, the sky is desolate, and only Asuka lies beside him — alive, or something like it. Shinji reaches out and strangles her. She does not resist. Then, she touches his face. He stops. She speaks one final, haunting line:

“Kimochi warui.” (「気持ち悪い」) — “How disgusting.”

This moment has spawned endless interpretations, and rightly so. But in its ambiguity lies a parallel philosophical thrust in Evangelion: the affirmation of being even in the face of disgust, pain, and failure. This is seen in the explanation of Yui’s decision by her sexually jealous teacher, Fuyutsuki, who says: “Humans exist because they have the will to live.... And that is the reason she remained within Eva.” Yet, despite this will-to-life element so strong around Shinji, he doesn’t seem to submit finally to the will-to-power. Rather, the “resolution” of his narrative as depicted within Evangelion, while not redemptive in the classical sense — there is no fanfare, no reward — is given meaning by his claiming for himself not power, not victory, but the right to suffer. The right to be an “I” in a world of others. The right to experience rejection, imperfection, embodiment, longing — and to still exist. It is a re-expression of reality after metaphysical dissolution, a re-enacting of the failure and terror of human connection, violently reasserting identity and separateness, and expressing accumulated trauma all in a final moment.

This return is not itself Christian in its final acceptance of suffering, but rather it echoes existentialist themes found in Sartre and Camus: that in the face of absurdity, we ought to still choose to live — although within the symbolic framework that the series sets up for itself, it is movement that allows one a closer space to God than what was originally afforded. For this final move does point towards the Christian concept of kenosis — the voluntary emptying of divine self into vulnerable humanity. If Shinji’s choice has symbolic overtones for the Christ, it is not because he saves the world, nor because he is virtuous or follows the Good in any capacity, but because he takes a step, however minute and infused with wickedness, towards the embrace of the cross of selfhood in a shattered cosmos.

This closing represents also one of the major themes in Evangelion: the failure of subjectivity — the inability of characters to relate as full, autonomous persons. Shinji, Asuka, Rei, and Misato all experience themselves and others through projection, fear, and need. This mirrors psychoanalytic insights about alienation and false identification — but it plays out with deep gender asymmetry because of the fact that the subjectivity of the work is itself ultimately only fully symbolically re-presentative of the one creator, Anno himself. Thus, the hypersexualization of teenage girls in moments of extreme vulnerability, the objectification of Rei and Asuka by both the narrative and the camera, the complex but troubling sexual politics surrounding Misato’s caretaking of Shinji, the hospital scene in The End of Evangelion — in which Shinji masturbates to Asuka’s unconscious body — are seen as irredeemably exploitative. This latter moment has rightly drawn widespread condemnation. The film offers no defense. Shinji is ashamed. The act is portrayed as pathetic, horrifying, and cruel. But again: representation does not equal endorsement — yet it undeniably traumatizes the viewer, and especially those who see themselves in Asuka. But still, as the philosopher Masahiro Morioka states,

Anime can portray movement, and nearly all of the women who appear in Neon Genesis Evangelion, for example, wear micro-miniskirts. Among these short skirts, the micro-mini worn by the character named Misato Katsuragi is particularly striking. We must not overlook the fact that the women who appear in this animated masterpiece, a work that skillfully depicts the struggles deep in the hearts and minds of young people, all wear miniskirts. New generations of men form their sexuality through such animated series; as long as they have female characters like Misato Katsuragi, they can feel powerful desire even without a flesh and blood woman.7

Thus, even in “critiquing” this mode of desire, Evangelion still participates in re-producing it: yet another movement of the way in which symbolic desire is inscribed into mythmaking in general, and even the most “radically postmodern” works cannot escape this basic function. Thus, the question of traumatic depictions of this kind of sensual representation may be producing desire by way of trauma. This is because nearly any depiction of the opposite gender in any form can reproduce desire, and thus this question of desire and its re-production becomes one of the preconditions for dealing with works featuring any kind of romantic, sensual or feminine depictions of beauty.

However, it seems that the real question at the heart of this kind of reproduction of desire is: to what extent is the production of desire within Evangelion sexist in its worldview, or does it portray the reality of sexism in a broken world? Does it reproduce a power fantasy, or deconstruct it? The answer, ultimately, may be both. But, what is the cost of such ambiguity? As we have already said, the Evangelion franchise is one dealing with the problems facing man in the 21st century, yet their “resolution” is never truly final, but rather the movement of crawling, however hideously, out of this problem and towards a life truly worth living. The franchise doesn’t try to utilize hideousness out of a need to add an edgy element around this journey to make it seem “deeper,” but rather is itself a part of the process of meaning-making itself, and not its end product. Thus, the ugly elements are fully “integrated” as the waste of the carving process itself.

Indeed, in addition to Asuka, Rei is quiet, blank, passive — an enigmatic figure who obeys without resistance. She is simultaneously mother (as a clone of Shinji’s mother), daughter, love interest, and sacrifice. Her nudity is shown often, without commentary. Her identity is essentially constructed by Gendo Ikari and NERV as a literal object. But in the internal logic of Evangelion, this is not celebrated. Rei is ultimately discarded, replaced, and erased — until she chooses to act on her own volition in The End of Evangelion, rejecting Gendo and fusing with Lilith on her own terms. Her liberation is not triumphant, but it is a rupture in the cycle of control. Thus, Rei’s objectification is depicted, but not endorsed. Whether that distinction is meaningful or ethically sufficient is precisely what remains under debate.

Misato embodies a psychosexual contradiction: mother, boss, and erotic object. She oscillates between maternal tenderness toward Shinji and boundary-blurring intimacy, especially in The End of Evangelion, when she kisses him before sending him to his possible death. Is this a violation? A symbol? A desperate attempt at connection in a collapsing world?

A major fault line in the best critique of Evangelion lies in the show’s use of “fanservice” in the original series through the use of constant revealing angles. These elements are unquestionably present, and often deeply uncomfortable. Critics ask: Why include these shots at all? If the narrative is about trauma and disintegration, why visually fetishize the very bodies that are being spiritually broken?

One interpretation is that Anno is indicting himself along with the audience: showing the despicable reality of their gaze. The hospital scene is not sexy. It is repulsive. Misato’s seductions are not erotic. They are devastating. Asuka’s breakdown is not a fantasy. It is collapse. But even if the intent is critical, the effect is still exploitative. The image is there. In attempting to critique objectification, the show still ultimately re-inscribes it. This is the tightrope Evangelion walks — and often stumbles on.

Another way to view the apparent sexism in Evangelion is through its spiritual poverty — the near-total absence of wholeness, especially in maternal or feminine form. Yui Ikari is gone — reduced to a ghost in the Eva; Asuka’s mother is dead, mad, and fused with her daughter’s weapon; Misato is motherless, and becomes a failed mother in turn; Rei is born from the remains of a woman long dead; and Lilith, the primordial feminine, is crucified and dismembered. But alongside this absence is a tangled presence: the feminine remains, fragmented and haunting, bound up with Shinji’s confused, often disgusted experience of sexual awakening. His intimacy with the women around him is fraught — he lives with Asuka like a surrogate spouse, is seduced and scolded by Misato in maternal turns, and confronts Rei as a distant echo of both mother and doll. This is not simply misogyny, but a Freudian nightmare of adolescence, where the failure to differentiate maternal love from sexual desire becomes a source of horror. The women are confused, manipulative, or hollow; Shinji is repulsed by his own drives. To read this as a critique of women is to miss the deeper loss: Evangelion depicts a world deprived of the sacred feminine.

The show does not glorify this absence — it grieves it. But it does not know how to restore it. The feminine remains alien, unstable, wounded, and in some cases, discarded. Shinji’s ultimate redemption does not come through reconciliation with the feminine, but through individuation.

In this sense, Evangelion is not anti-woman, but anti-wholeness — a condition reflected not only in the loss of the sacred feminine, but in the arrested development of every character’s ability to form loving, mature relationships. The price of that psychic rupture is borne most violently by the women onscreen.

The wound is real. And no interpretation can undo it.

But, it seems that it hopes it can teach. Not as an example to imitate, but as a mirror of what happens when gender becomes a means of abusive self-medication when no one has the tools to heal.

5. From Fall to Kenosis: Existential Return and Meta-Modern Hope

Neon Genesis Evangelion is not an easy work. It is self-contradictory, opaque, sometimes indulgent, sometimes cruel. It does not provide a map, but it dramatizes the act of mapping: the search for meaning, the fragmentation of inherited symbols, the terror and necessity of choice.

This is the meta-modern mythology of Evangelion: not a narrative that explains the world, but a ritual that teaches us to stand in the ruins and begin the work for ourselves.

The internal narrative and symbolic structure situating the initial few passes at Evangelion within its cultural matrix (1990s Japan) reveals an era of economic collapse, declining social cohesion, and the birth of what cultural critic Hiroki Azuma famously called the “database animal.” Evangelion does not merely reflect this cultural milieu — it embodies its psychic condition.

The series was a revolution, but also a wound. In dismantling the tropes of mecha anime, in exposing the broken psychology beneath the mask of heroism, Evangelion broke open the genre itself. It turned inward to reveal the fragmented, the failure of the system to resolve itself, and the scream of loss and groping for meaning.

And the audience — particularly the otaku subculture — felt this rupture. They responded with obsessive analysis, fervent devotion, and in some cases, violent backlash. This tension reveals something crucial: Evangelion was not a closed artwork. It was a wound that demanded healing — a rupture in the symbolic order that could not be ignored. Anno, in turn, responded not with retreat, but with recursion. Hence, the Rebuild films.

Between 2007 and 2021, Hideaki Anno released the Rebuild of Evangelion tetralogy: a four-part cinematic reimagining of the original series. Beginning as a faithful retelling, the series gradually diverges into radically new territory, culminating in the emotionally resonant and narratively redemptive Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time.

The Rebuilds are not simply remakes. They are meta-artifacts, each film a recursive engagement with the original text, audience expectations, and Anno’s own artistic psyche. The first film (1.0) is nostalgic and reverent. The second (2.0) becomes exuberant, almost utopian in its treatment of characters and romance. The third (3.0) collapses into disorientation and nihilism — a deliberate sabotage of the heroic arc. And the fourth (3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time) — astonishingly — resurrects narrative, possibility, and peace.

Where the original Evangelion ends in ambiguity, fragmentation, and despair, Rebuild ends in a clearing. Shinji grows. He takes responsibility. He chooses not merely to live, but to release others from the cycles of trauma and repetition.

A central theme of Evangelion’s cultural critique — especially in the Rebuilds — is the prison of repetition. The endless loop of simulacra. The consumption of tropes devoid of grounding mythos.

In Azuma’s terms, otaku culture post-1980s operates not with linear narratives, but with databases of tropes, archetypes, and “moe elements.” Plot becomes less important than emotional triggers. Identity fragments into aesthetic preferences.

Evangelion is both a product and critique of this system. The original series deconstructs these tropes. The Rebuilds, especially 3.0, confront the horror of repetition: the same scenes replayed, the same traumas re-experienced, the same characters locked in symbolic stasis.

But Thrice Upon a Time offers something new. It does not merely deconstruct the loop, but provides the foothold towards a “way out.”

In doing so, it issues a profound call: to leave the cage of nostalgia, to grow up, to step into the world.

Across its multiple versions, Evangelion dramatizes a cultural and spiritual transition — from disenchantment to the tentative re-enchantment of a disenchanted world. This trajectory maps perfectly onto the emerging philosophical condition of meta-modernity.

Meta-modernism does not reject irony, but moves through it. It affirms sincerity after cynicism, faith after fragmentation, myth after deconstruction.

Where the anime frequently walks the line between critique and complicity — offering fanservice-laden shots that blur into trauma and objectification — the manga largely refuses to participate in that visual economy. The Neon Genesis Evangelion manga has a unique and somewhat paradoxical origin story — developed as a promotional companion to the anime, yet written and drawn by the series’ original character designer, Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, who had considerable freedom to reinterpret the story. It began before the anime aired, but outlived it by over a decade, eventually becoming a parallel version rather than a direct adaptation. Sadamoto slows the pacing, offering more interior monologue and psychological development, softened or altered characterizations: Rei is more emotive, Asuka more vulnerable, Shinji slightly more assertive; plus he eliminates or revises controversial scenes. The work preserves the existential and emotional stakes of the original but channels them through a slower, more humanistic lens, rather than the sort of Max Stirnir–esque egoism of the original. It gives the characters more room to breathe, grieve, and grow — especially Shinji, whose final act in the manga is to choose connection and reconciliation without the cataclysmic rupture of The End of Evangelion.

6. Christianity as Answer to the Cry

To return finally to the question of the controversial usage of religious imagery: crosses, angels, a “Tree of Life,” Lilith, Adam, even “instrumentality” as a form of deification — as any moderately conscious viewer or reader of Christian theology can tell, these symbols are evacuated of their traditional referents. In Evangelion, the cross no longer points to resurrection but to annihilation. The “angels” are not messengers of divine peace but monsters of uncertain origin. The divine is not incarnate, but absent. God is never spoken of as a Person — only as an evolutionary hypothesis or biological force.

But in the late space of Modernity, where Evangelion dramatizes the trauma of meaninglessness and the human longing to create connection in a world stripped of God, this symbolism can parallel the phenomenon markedly referred to as “The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God” (Justin Brierley’s title). Christianity, that religion whose symbols saturate this work, begins with the fullness of God’s presence, and the invitation to participate in that fullness through love, communion, and self-emptying. Where Evangelion exposes the scars of postmodernity, Christianity offers a vision of transfigured humanity rooted in tradition, theosis, and personal communion with the divine.

In Evangelion, human nature is essentially fragmented. From the very beginning, the series assumes a psychoanalytic anthropology: the self is a fragile construct made up of projections, trauma, fear of abandonment, and the need to construct identity through the Other. This is existential anthropology in the key of Sartre or Lacan. The “hedgehog’s dilemma” — used as a motif early in the show — suggests that human closeness inevitably wounds, that intimacy is always dangerous, and that perhaps the best one can do is maintain some tolerable distance.

Christianity, while not naïve about the brokenness of human nature and the pain that inevitably occurs in this life, still posits a radically different starting point: man is made in the image of God, which means the human person is inherently relational, good, and oriented toward communion. The problem is not proximity, but self-will and sin, understood not merely as moral failings but as existential alienation from the divine source of life.

Where Evangelion says: “We are alone, and trying to merge only leads to terror,” Christianity says: “We were made to be united in love, and sin is the distortion of this capacity.”

In short, Evangelion dramatizes the Fall without a Creator and without grace. It offers no original unity to which we might return — only scattered fragments, stitched together by longing. In the Lacanian vision, the Real is filled with “antagonisms all the way down.”

The Human Instrumentality Project is Evangelion’s closest analogue to religious salvation. It promises to dissolve all boundaries between people, creating one unified consciousness where no one suffers, no one is rejected, and no one is alone. In short: it is simultaneously a technological and Buddhist representation of heaven from their own metaphysical viewpoints, which are both essentially mere parody.

Instrumentality is, by Christian standards, a false eschaton. It obliterates the person in order to eliminate suffering. There is no communion — only the annihilation of difference. However, this is obvious foolishness. The observation that desire leads to suffering is made a mockery when, rather than daring to redeem either, one chooses merely to dissolve the sufferer. Buddhism may call this liberation, but it’s fairly easy to see why those outside of this system would perceive it as spiritual suicide wrapped in the language of wisdom. The Buddhist vision seems to be in agreement with the childish trick of Descartes. “I will strip away everything, except for reason,” says the “philosopher,” and then, “behold! I have found that I must exist in order to use reason! Therefore, I am equivalent to the reasoning being itself!” But of course, this is not knowledge. It is disincarnate rationalism — a cartoon of personhood. And is this not the foundational concept of the Enlightenment? How is this different from the Buddhist notion that you suffer because you are conscious, that you struggle because you exist? If this is true, why wouldn’t the logical next step be to stop existing?

In Christianity, is this not the same thing the demons tempt with? Is this not the message of acedia and despair? “You are the problem. Erase yourself. Step into the void and be free.”

This is not enlightenment. It is a metaphysical euthanasia. What is annihilated through Catharsis is not the inner person, but rather the entirety of our egotism and its passions which obstruct Love, Goodness, Truth, Charity, etc. This is why the notion of theosis — deification — is rooted in love and the preservation of personhood. To become “one with God” in the Christian sense does not mean being absorbed into a cosmic soup. It means becoming fully yourself by participation in the divine life, while retaining your uniqueness. As St. Maximus the Confessor writes:

If an intellective being is moved intellectively... then it will necessarily become a knowing intellect. But if it knows, it surely loves that which it knows; and if it loves, it certainly suffers an ecstasy toward it... [so that] it will not cease until it is wholly present in the whole beloved, and wholly encompassed by it... receiving the whole saving circumscription by its own choice... and, being wholly circumscribed, [it] will no longer ... wish to be known from its own qualities, but rather from those of the circumscriber, in the same way that air is thoroughly permeated by light, or iron in a forge is completely penetrated by the fire.

And,

Let not these words disturb you, for I am not implying the destruction of our power of self-determination, but rather... a voluntary surrender of the will, so that from the same source whence we received our being, we should also long to receive being moved, like an image that has ascended to its archetype, so that henceforth it has neither the inclination nor the ability to be carried elsewhere…; it is no longer able to desire such a thing, for it will have received the divine energy — or rather it will have become God by divinization... showing that it has God alone acting within it.8

And, as we have previously stated, although Evangelion is replete with Christian imagery, the imagery is often empty. Its presence is not there merely because it is exotic to Japanese audiences, as its creator claims, but also because it functions as a key element of the dirge moving the philosophical cry of the work.

The sacred grammar in Evangelion reveals the deep mourning that its “emptiness” represents to the despair in the work. It’s not a “post-Christian” work which has failed to believe any longer in the narrative of Christianity, but rather the Christian language functions as a failed signifier for the total loss of sacred meaning. The promise of meaning still being available through participation in the mystery of the Cross is felt in the series, but is in no way understood. The traumatized may be resurrected through the Nietzschean cycle of the Eternal Return, and thus the transfigured stands out, over and against this tragedy.

Neon Genesis Evangelion doesn’t teach theology — how could it? — but because it stages the ache for theology in a world where God has become a cipher, it is the howl of postmodern man confronting the abyss, searching for a mother, a father, a friend — anyone to confirm that he is real and loved.

In this way Christianity stands not as a rebuttal, but as a response: not to explain away Shinji’s pain, but to proclaim that even in the heart of that pain, God has entered in. That the cross is not merely a shape on the screen, but the place where alienation is crucified, and love is raised.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is a profoundly hybrid work — religiously, aesthetically, and philosophically. While its Christian iconography is most visually prominent, its deepest metaphysical and narrative structures are arguably more indebted to Japanese religious traditions: Buddhism (particularly Zen and Pure Land) and Shinto, the indigenous animist spirituality of Japan.

What emerges in Evangelion is a synthetic spiritual ecology: Christian forms emptied of doctrine, Buddhist meditations on selfhood and emptiness, and Shinto resonances with purity, the spirit world, and maternal immanence. These traditions are not harmonized. They are placed side-by-side in tension, in crisis — reflecting the fractured psyche of postwar Japan, and, more personally, the inner landscape of Hideaki Anno himself.

Yet Anno seems to have spoken very clearly to a group who, like him, grew up in a time disproportionately affected by depression, anxiety, climate dread, and institutional disillusionment. Evangelion’s emotional register feels uncannily prescient. Shinji’s paralysis, his need for external validation, his loathing of himself for desiring connection — all resonate with the internal landscape of those Gen Xers and Millennials who grew up with new media, with anime, with the growing space of “fandom,” whose psychic inheritance includes both digital overexposure and emotional detachment. And yet, through this dark aestheticization, a deep longing emerges: for meaning, for integration, for love that does not destroy.

There’s a continued growing online culture steeped in “trauma-core” — an aesthetic style that blends nostalgic visuals (VHS fuzz, lo-fi anime stills, children’s TV) with messages of pain, depersonalization, and longing. Evangelion is ground zero for this space.

These visual motifs are deployed with post-ironic precision: the line between joking and prayer blurs. Gen Z grew up on the ruins of postmodern irony — but also after the failure of that irony to protect them from emotional erosion. What Evangelion offers is a perfectly meta-modern vessel: a work that critiques its own existence, that weeps behind its tropes, that simultaneously mocks and honors myth.

This is how myth operates in the 21st century: as open-source sacred narrative. And Evangelion is the most editable of works. And maybe more importantly — it is a starting place.

Linked Articles & Posts

Linked Premium Articles & Posts

1. “About Neon Genesis Evangelion,” Newtype, reprinted in Protoculture Addicts, no. 43, Nov. 1996.

2. Claude Lévi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology, td. by Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf (Basic Books, 1963), pp. 210–211.

3. Jonathan Pageau, “Diving Into Dante's Divine Comedy,” YouTube, December 3, 2020. Here I speak of the “personal narrative” of a nation in order to highlight the notion that Pageau, Fr. Stephen De Young, Fr. Andrew Damick and others have noted concerning the life and spirit of a nation being something more than just a figure of speech. See Jonathan Pageau, “Do Principalities Have Will and Perception? | Clip from September Patreon Q&A,” YouTube, September 21, 2018; and the Lord of Spirits podcast, “Angels and Demons II: The Divine Council,” September 24, 2020.

4. For examples of the archetype of reluctant teens who are afraid of war piloting giant mechs, see Brave Raideen (1975), Mobile Suit Gundam (1979), Super Dimensions Fortress Macross (1982), Aura Battler Dunbine (1983), Space Runaway Ideon (1980), Dancouga – Super Beast Machine God (1985), and Gunbuster (1988). Although Evangelion does not reject its mecha predecessors, it collapses their heroic arcs: where Gundam offers competence, it gives us psychological breakdown; where Macross celebrates love and courage, it leaves them wounded and frail; where other protagonists mature through action, Shinji retreats into paralysis. It is their deconstruction and requiem, reborn as psychoanalytic, spiritual, and existential myth.

5. David Samuels, “Let’s Die Together,” The Atlantic, May 2007, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2007/05/let-s-die-together/305776/.

6. Hiroki Azuma, “Database Animals,” Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World, ed. by Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe, and Izumi Tsuji (Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 43–68.

7. Mitsuhiko Yanase, Confessions of a Frigid Man: A Philosopher’s Journey into the Hidden Layers of Men’s Sexuality, td. by Christopher Holmes (iUniverse, 2004), p. 20.

8. Maximos the Confessor, Ambiguum 7.10–11, in On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Volume I, td. by Nicholas Constas (Harvard University Press, 2014), pp. 87–91.

MEMBERSHIP

Join our Symbolic World community today and enjoy free access to community forums, premium content, and exclusive offers.

.svg)

.svg.png)

Comments